I think Radley Balko is onto a great strategy to promote liberty. It's basically the same strategy non-libertarians (statists, alarmists, public healthists, public safetyists, etc.) have been using for years. The strategy? Focus on the personal victims of whatever evil you're trying to expose. Think about it...for smoking ban advocates, it's stories about the poor single-mom waitress who has lung cancer despite never smoking a day in her life after working at a restaurant (where smoking is allowed) for 30 years. For the MADD crowd, nothing's more effective than the infamous "Happy Birthday" commercials where a home video of a child's birthday party is shown while a narrator informs viewers that the child was killed by a drunk driver. For food safety alarmists, it's not the fact that 15 out of 300 million people got sick from eating bad spinach, it's that the old man is in critical condition at a local hospital after eating a salad.

Libertarians and free market advocates know they're right in the grand scheme of things. It's not even close. Look at things like global standards of living, then look at levels of economic, social, and press freedom. On the macro level, it's clear that greater liberty equals a better society for all. On the macro level, the few people who actually care enough to objectively consider the macro-level generally accept this idea.

But on the micro level, where most of the people (most of the voters!!) make their decisions, the non-libertarians dominate. When was the last time you saw a local (or even national) news story that focused on the abuse of power by government and/or how government hurts people's lives. Rarely. And if there is such a story, it's usually couched in terms that make the government's co-conspirators (such as a money-hungry corporation) look worse than the government. What's far more likely is a story about how some business or landlord is ripping people off, how someone died because of "gun violence," or some victim-laden story about the "digital divide" or the growing gap between rich and poor. And almost inevitably the stated or implied solution to such problems is more government action.

Anyway, back to the lecture at hand. "If it bleeds, it leads." That's the de facto axiom of news broadcasts. Why? Because people sympathize with personal stories. It doesn't even really matter what the story is; if there's a personal story with a likable person as a victim, it's perfect for the news.

And I think that libertarians are finally realizing this. Radley Balko is leading the charge at using personal stories to illustrate how government policies and government corruption can ruin the life of a real, actual person with a face and a name. Finally libertarians are understanding that what sells are personal stories on the micro level. You can talk all you want about how increased economic liberty will lead to a better society for all, but that point gets lost on most of the audience. What really gets people are real-world examples of individual victims.

Saturday, December 23, 2006

Friday, December 1, 2006

Design For Not Needing To Be Fixed

I finally fixed the door knob for the door going between the garage and my house (for the last couple of months I had just taped the latching mechanism opened so that I wouldn't have to deal with it), and I discovered that the door knob has a really obvious design flaw. But first some background.

I finally fixed the door knob for the door going between the garage and my house (for the last couple of months I had just taped the latching mechanism opened so that I wouldn't have to deal with it), and I discovered that the door knob has a really obvious design flaw. But first some background.Background

A couple of months ago, I attempted to open the door going to the garage from inside the house. To my surprise, the knob turned, but the door didn't open. I kept turning the knob, and nothing happened...I quickly deduced that the knob wasn't mechanically coupled to the latching mechanism, so turning the knob would do no good. Since the only other way into the garage was through the garage door openers inside the cars that were parked inside the garage, the only way I could get into the garage would be to somehow open the door. Luckily, after a couple of attempts, I was able to pry the latch open by wedging a butter knife in-between the latch and the slot in the door frame into which the latch moves, and I got the door open. Since I was in a hurry, I simply put a piece of tape over the latch to prevent it from going back into the slot when the door closed.

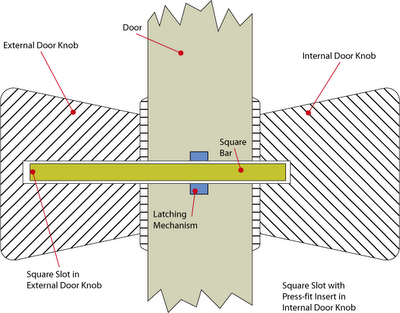

Later, when I removed the entire door knob assembly, I figured out that the way the knob was coupled to the latch was with a simple square (square in cross-section) bar. As the diagram below shows, the Square Slot (in which the Square Bar resides) in the Internal Door Knob has an extra little feature that the Square Bar press-fits into. The square bar travels through the Door, through the Latching Mechanism, and into the External Door Knob. Turn either knob, and the square bar to which the knob is rigidly fixed turns the latching mechanism and just like that, the door unlatches.

After looking at all the parts of the door knob assembly, I realized that to fix it, I'd simply have to re-rigidly-fix the square bar to one of the door knobs. This was easy enough, and in just a couple of minutes the door knob was back on the door, fully functional.

The design flaw

So what's the big deal? Well, this whole charade could easily have been avoided if the door knob were better designed. The following diagram shows what the door knob system looked like when it was broken.

As stated above, the problem is that the Square Bar had become de-coupled from the Press-fit Insert in the Square Slot in the Internal Door Knob. But what really made matters worse is the fact that the Square Bar was too short! As the above diagram shows, since the Square Bar was so short, once it became detached from the Press-fit Insert it was able to float freely, and eventually it moved such that turning the Internal Door Knob would no longer actuate the Square Bar. Plus, the fact that the only way the Square Bar can be coupled to the Internal Door Knob end of the Square Slot is via a press-fit, there's no way the Square Bar, once loose, would ever incidentally fall back into the Internal Door Knob.

The solution

The solution to all of this madness would simply be to make the Square Bar longer. In fact, it should be almost as long as the entire Square Slot. This would alleviate the need for the extra Press-fit Insert, plus there would be no way for the Square Bar to become decoupled from either the Internal or External Door Knobs. The following diagram shows the proposed solution.

Simple is better.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)